|

This National Park seems to nicely travel along the Danube with you - from Esztergom all the way to Budapest, it is always there or nearby, a friendly but unobtrusive touch on the shoulder. Unobtrusive… if you don’t know about it while riding the EuroVelo 6, it will silently stay aside in the hills above the river, in Pilis and Visegrád mountains, in the Börzsöny range, on islands, wetlands, and floodplains. There is a lot of hidden beauty here, just a short train ride away from Budapest.

Where that second part of the park’s name comes from? Ipoly (Ipeľ) is a 232 km long Danube tributary with the source in central Slovakia (Ore Mountains) and the confluence near Szob in Hungary. One part of its valley, between the towns of Hont and Balassagyarmat, belongs to the National Park.

Established in 1997, it is the ninth and the youngest, but at the same time one of the most diverse national parks in Hungary. Besides its area of 60,314 ha, the Park’s Directorate also takes care of 8 Protected Landscape Areas, 32 Nature Conservation Areas, one area recognized by a European Diploma for Protected Areas and a Biosphere Reserve of Pilis mountains. It is also part of the EU Natura 2000 nature and bird protection network. The uniqueness of the park comes from a mixture of three different landscape types: river valleys, mountains, and lowland. Of its 191 species of birds, 40 are protected by law. Some species of flora and fauna have their sole habitat here.

The Directorate has to find ways to save these rare and endangered species, protect the integrity of the wildlife, plan and implement the conservation measures, and let’s not forget the preservation of cultural and historical values – all this (a bit similarly to the Wachau region) in the crowded central part of Hungary and amidst dense infrastructure and industry, including Budapest. So expect some magic to be unveiled later here :)

One interesting development is that there are now more and more signs of habitation by Eurasian beavers and lynx, two species which had previously disappeared completely in this region.

The region is the cradle of numerous cultural values as well. Traces of prehistoric humans have been found in the caves, while the Börzsöny is home to Drégely Castle, an important site in Hungarian history. Fine examples of medieval ecclesiastic architecture include the ruins near Pilisszentlélek and the monastery of the Order of St. Paul at Márianosztra. The Park also has local historic houses and museums which present the culture and life of the region's German minority, which was settled in the area in the 18th century.

The emblem of the National Park bears an image of a rosalia longicorn, which is associated with old beech forests as its larvae develop in the rotting wood of dead trees. Its wings are brilliant steel-blue and black, and its long antennae bring to mind a string of pearls. It is a protected species, known as Rosalia Alpina. The choice of the emblem also symbolizes that the mission of nature protection is to safeguard life in all its forms.

To start my visit to Esztergom’s part of the Park I needed to cycle 6km out of this charming historic town. Then I came to the Kökörcsin Ház (“Anemone house”), the headquarters of the NP, where I met Szilvia Németh and Gergely Kálmán.

With his University degree Gergely started a career in the park as a tour guide six years ago, then after three years became a communication officer at the park’s Department of environmental education. His job is to introduce values and qualities of the Park to visitors, and to explain to the public why their measures and actions are important: “This is one efficient way to provide nationwide support for our activities and to be sure that enough people will always stand behind us.”

DANUBEparksCONNECTED gave Gergely a chance to check how the public relations strategy was applied in Fertő-Hanság and Kiskunsági National Parks, while Djerdap NP is currently on his wishlist.

The area definitely has an interesting past: In the first place, I was surprised to learn that the Ottoman occupation of Esztergom region lasted for 150 years. That long? Phew…now these 300 years of Ottoman occupation of Serbia seem a bit more… acceptable.

And then: the spacious, hill zone around the Kökörcsin Ház was used as a military exercise ground since the end of WW I well until the nineties of the last century when Russian troops left the region. And the house itself was actually built to be the officer's headquarter. And the concrete surface on the parking lot is 60 cm thick – it was made to bear the weight of the tanks. And the nearby small lake is called Killer lake: it was used to practice operating tanks underwater and one day a complete Russian crew in one of them drowned.

And… and today it is a Protected Area (*) that sees 3000 visitors per year, mostly school children. There is space to accept 50 of them at a time, for an educational stay. There is an exhibition on the second floor of the house, presenting values of the area.

(*) There are two levels of nature protection in Hungary: Protected Area and Strictly Protected Area. Visiting a SPA is allowed only with the escort of the rangers.

The whole Danube in Hungary is declared as a Natura 2000 zone. (But an interesting fact is that the PA’s of Hungary provide a higher level of protection than the Natura 2000 zones.)

Maximal penalties for damaging and destroying protected species of flora and fauna in Hungary are in the range of 3000 EUR, and the worst cases might include imprisonment. But while the maximal penalty for the white-tailed eagle is something that one could expect, the intrinsic values of some other protected animals can be quite surprising. For example, the “worth” of brown bears or wolves is under 800 EUR, while one species of humble (but very rare) forest mouse is in the same category as the white-tailed eagle - 3000 EUR. To see more check this page.

My hosts took me to the Strázsa (“Patrol”) hill Study Trail. All hills in the region are Triassic, 230 million years old limestone formations and the highest of them has an elevation of 730 m. Strázsa is much lower, but approves its name: one can scan large distances from its peak. Before reaching that point we experienced a diverse landscape: first treeless and sandy grassland, then shear strength of a karstic cliff with its characteristic shrubs and including a quarry that was used until 100 years ago. There were several protected plant species along the way.

On the Strázsa hill Study Trail

Reminders of the past

View of Esztergom from the Strázsa hill

The observation tower on the top of the hill was built by Soviet troops

Szilvia and Gergely

Except for this walk, Kökörcsin Ház offers to visitors the “Bunker” tour: you can visit a few of these interesting remnants from the area military past.

We walked a bit more through the fine landscape behind the Strázsa hill. After a few days of strong rain, spots of dainty purple color here and there marked Szilvia’s and Gergely’s bellowed “pets”: orchids. Happy and passionate, they knew the exact place even before we would arrive there, and after a while I was curious did they even give a name to each of the plants. A bit of giggling and then I got this confidential information: “Orchids have some kind of a character and they are a bit mysterious too. They disappear for a couple of years - sometimes even for six, seven years - and then come back. This one here, for example, reappeared this spring, after two years.”

Checking an old bunker The purple beauty

Between 1914 and 1918 one of the largest Prisoners of War camps of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was located in the military exercise field surrounding Strázsa Hill. Many of the prisoners were victims to epidemics and were buried in eleven cemeteries - this is the Cemetery No 7, with graves of 1548 Italian, Romanian and Serbian prisoners. When the Soviet army took over the area, the cemetery was neglected and gradually covered by scrap. It was cleaned and renovated from 2007 to 2009 with the joint effort of the Hungarian Institute and Museum of Military History, Ministry of Defence, Municipality of Esztergom, Cultural Society "Honved", Duna-Ipoly NP and a number of volunteers. Among participants at the opening ceremony on 1st July 2009 were representatives of Italy, Russia, Romania, and Serbia.

Signposts in the Protected Area

Back to the Kökörcsin house for a quick walk to the Killer lake before saying goodbye to my hosts. Its water level is observed and adjusted by the Park’s staff, but at this moment it was empty: the local government was financing cleaning its bottom from metal artefacts (again, remnants from the military past).

Szentendrei island

After cycling from Esztergom, past the former royal seat Visegrád and its impressive castle, I took a short boat ride to Kisoroszi - a small village at the western end of the Szentendrei island, right in the Danube Bend.

The plan was to meet Gergely again next morning for a cycling tour, but I decided to use the rest of this day to visit the western tip of the island: it looked promising on the map. And it was a lucky decision - those late afternoon hours turned to be among the most beautiful on the whole Danube trip. The late sun turned pebble shores into a gold mine with smooth, huge nuggets all around. And it was impossible to get enough of the picturesque panorama of riparian forest, permeated by shadows and shallow water, nor it was possible to leave it with a glad heart to the melting power of incoming nuances of the night.

Next morning I rode to Tahitótfalu, a small town that is, like Budapest, very logically :) divided by the Danube to Tahi (the mainland part) and Tótfalu (the island part). Tótfalu and its sandy soil surroundings are famous for wines but maybe even more for growing strawberries.

A small band for the island cycling experience included Gergely, the Park ranger Balázs Fehér, and Sasha Draskovic, a friend from Budapest.

There are 30-35 rangers in the Danube–Ipoly NP but that is still far from enough, considering the Park’s size. So each ranger covers a huge space: Balázs, who works in the Park for six years, takes care of a territory that covers seven villages and has an area of - 60.000 ha (!) That is why his shift usually means a week or more of a constant presence in the field, and he doesn’t return home during this time.

The first interesting thing to see on the island was one of its sandy zones, nowadays used for grazing. The fine sand here was covered with naturally grown bushes and shrubs. This was home for many protected plant species, including feather grass (Stipa borysthenica), a post-glacial relict and an endangered species. “People used to pick it just because it looked nice and they wanted to take it home”, says Balázs, “But education helped to change that habit a lot.”

A landscape with the feather grass

Despite being close to densely inhabited areas, the island is not under pressure of illegal construction (unlike the hilly regions of the Park):

“We generally get on well with local people, there is sometimes just a lack of knowledge about the Park rules and regulations. For example, some don’t know that they must have a permit for grazing and haymaking. But this is a Natura 2000 zone and that entails certain conditions for human activities. Haymaking will start after orchids finish flowering – within a month, their flowers and leaves will disappear, leaving only underground tubers that will be safe from cutting tools or moving machines. Grazing begins in June, and it will be only horses. It is not that we specifically favour this sort of domestic animals - the situation is that the local person who uses these pastures keeps only horses”, explains Balázs.

The biggest wild animal in Hungary? Yes, the scale goes up to bears. Last year one entered the country from the Czech Republic (that is also where wolfs usually come from) and it was a big media news. The bear managed to go quite far southwards before being caught, marked with a tracking device and transported to the mountains in the north. But Hungarian forests are generally not big enough to provide the “full comfort” to a bear.

At an old branch of the Danube. This was an island and the river was flowing here before sedimentation closed the passage. Zones like this one are now very important for fish reproduction: there are species (carp for example) that spawn only in standing water.

There are a lot of invasive plants (pale green color on the photo) such as the Green Acer, that repress the original species, which is the major conservation problem on the island. Unfortunately, there is no efficient way to prevent this process. The approach with mechanization is very difficult, and clearing invasive plants wouldn’t help for long anyway – the Danube constantly brings new seeds.

The Szentendrei island is a very important source of drinking water for Budapest. This potential was discovered in the sixties of the last century, the land was nationalized soon after that and the arterial wells system that was built consists of hundreds of units. Each well is actually a vertical duct that goes 20-30m deep in the ground, and then there are thinner, 20-30m long horizontal side pipes that branch from the vertical duct. All wells are connected to a central collecting station with strong pumps that pull water from this arterial network. The water thus obtained is so clean that it does not need any processing, apart from adding a bit of chlorine to take care of eventual impurities in the city pipelines.

The arterial wells of Szentendrei island

Wells which are close to the Danube look like concrete submarines. They have “bows” reinforced with metal, allowing them to break the ice that the river might push during winter.

There is a phrase “the boy is born before father” connected to the Autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale) because it flowers first, then rests, and then makes leaves.

But there is another, very unpleasant characteristic of this plant: all its parts are deadly poisonous for humans, due to colchicine that it contains. This compound interferes with cell mitosis and is used for genetic research due to its huge impact on human cells - it stops their division. Symptoms are similar to those of arsenic poisoning, and no antidote is known.

And there is a theoretical line that could bring the plant to a human organism: if it is contained in the hay after mowing it could be consumed by cows, thus contaminating their milk.

The Autumn crocus

When 1.5 m of height makes all the difference: wetland below the dam and a half-desert habitat on its top.

The amount of plastic bottles in the Hungarian part of the Danube is decreasing. As for general pollution, the Danube cities are quite “friendly” while smaller rivers like the Tisza are a bigger problem. Budapest has a processing plant for wastewater, Szent Endre has its own, etc. (All these plants were built roughly 10 years ago after Hungary became an EU member.)

After informing me that the Park plans to build a large Visitor Center in Dömös, Gergely notes that cycle tourists who travel along the EuroVelo 6 practically don’t visit the Park. Which is really something to think about: it is necessary to specifically promote the Duna-Ipoly and other protected Danube areas both by European cyclist’s federation (who manages the EuroVelo routes), as well as by national EuroVelo coordinators.

The secret worlds of Budapest

A series of highly surprising discoveries in the Hungarian capital started in Buda Hills: right in the middle of a densely inhabited area whose streets were dotted with nice upper-middle-class family homes, close to a city public transport station, right there, just like that… was the entrance to Szemlőhegyi cave. Which sees 30-32,000 visitors per year. Just like that.

András Hegedüs, an NP employee and passionate speleologist, member of the Cave Rescue Hungaria and my host in the cave, looks young but he managed to pack in his pockets as much as 25 years of work experience. And his speleological history is even longer than that: he started early and chased caves in Hungary, France, Italy, USA, Romania, Montenegro, Serbia… (He greeted me with a nice basic Serbian vocabulary even on the phone, before we met.)

“The cave was discovered in 1930 and was opened for tourists in 1986. It is currently explored in a length of 2200 m and visitors can walk on about 250 meters of sidewalks and stairs. It underwent the last general reconstruction in 2013 when access was provided also for disabled people. The light system was improved in 2018, and since next year visitors will be able to watch 3D movies here.”

Being one of the most valuable natural treasures of Budapest and offering rich forms and ornaments, Szemlőhegyi is placed under increased protection. Such examples of pisolite precipitations and gypsum crystals are hard to find anywhere else in Europe.

Szemlőhegyi cave

No reflectors, no sidewalks, no stairs, no discrete music, no guides (and no entrance fee)

The clear and dust-free air of the cave offers a therapy to treat asthma and other respiratory organs problems: 2-3 hours a day / 2-3 times a week, with a doctor’s referral, and treatments are free. And while being there for medical or just tourist motives, one can see an exhibition showing the most important caves of the Buda Hills.

Caves, yes… There are more than 4000 of them in Hungary, and in Budapest, there are more than 150! Thus, not far from the Szemlőhegyi there was another one that sees as many visitors, but boasts the longest underground system of Hungary: Pál-völgyi cave channels are 33 kilometres long. And again, this unbelievable world exists right below the basements of a densely populated area of the Hungarian capital.

Pál-völgyi cave

Opened for visitors in 1990, the cave is famous for its unique dripstones and fossilized seashells and to András opinion it is the most beautiful cave in the Buda Hills. We walked a bit more than 300m, but there are tours for advanced cavers that are 3 km long.

The last surprise for Sasha and me was again just a short walk away: the upper part of the Sas-hegy (“Eagle Hill”, a translation of the former German name, “Adlerberg”) is actually no less than - a Nature Reserve. A tiny island of pure nature at 257 m of altitude, surrounded by the sea of concrete and civilization, the patch of wilderness that lingers amongst the tall buildings, complete with a visitor centre, guided tours, limited movement of tourists and a custodian to take us around.

“Well, Budapest is one of the richest cities in Europe when it comes to nature. Its flora is characterized by endemic species and there are Eastern imperial eagles only 30 km far from the city, in the heart of the Duna-Ipoly National Park”, says our guide Gulyás Kis Czaba, palaeontologist and geologist, a local volunteer and supervisor in the Reserve. And he took us on a narrow, unbelievable trail that was twisting on the top of the hill between limestone and dolomite formations and flora and fauna dating from the glacier era - all this with a near-360 degree scenic view of absolutely all famous and important buildings of the pulsating metropolis below us.

The zone with Sas hill separated during the ice age. Before that, it was a part of a warmer climate zone that was following the line Dunav – Vardar (in Macedonia). It is known that the territory of Pest (and most of what is today Hungary) was a marchland at that time, but the type of vegetation is unclear since it changed over the last 5000 years. There is only a small wetland area left today in the Pest zone and there are still reptiles, amphibians and other species typical for wetlands.

The circular trail is about 2km long and connects all corners of the 12 ha large Reserve above the slopes where, after the Ottoman occupation, German colonists planted orchards and vineyards. Since 1940s building of family homes and villas started to endanger that green zone, but during the WW II many of them were destroyed, especially during the siege of Budapest in 1944-45. (There is one old bunker on the trail that nowadays hosts a seismic station. And the curiosity is that the station was the first to register the recent nuclear bomb test in North Korea, thus starting an international crisis.)

Then in 1958 the hill was placed under protection and became one of the first nature reserves of Hungary. It was, however, too late for other nearby hills - they were already covered with houses. Some species - like bird Monticola Saxatilis (Common Rock-thrush) have vanished. And even that first protection of the Sas Hill was not very strong: the really efficient protection regime started in 1970.

The Eagle Hill trail: nature with a bonus urban insight

Czaba Gulyás

The Sas Hill actually has two peaks and one of them is strictly protected, due to its valuable Alpine and Dolomites plant species. Today one can find here species that remained from the warmer period before the Ice Age, side by side with those from the Ice Age.

The most iconic plant of the Sas Hill is the silver grass (Pannonian Bluegrass, Sesleria Sadleriana), dating from the glacier era. It normally lives at the altitudes of 1600-1700 m, in the Alps and Carpathians. During the Ice Age, it moved far south and returned afterwards but here, due to the separation, it was isolated at the altitude of 250m and became endemic.

There are also almond trees which are typical Mediterranean plants, but they were planted at the time of vineyards and there are still some of them left. Twenty years ago all non-native trees planted before the establishment of the Reserve were removed and they now monitor the situation. After all this time the process has not yet been completed - more time is needed to return the habitat to its original, very different state.

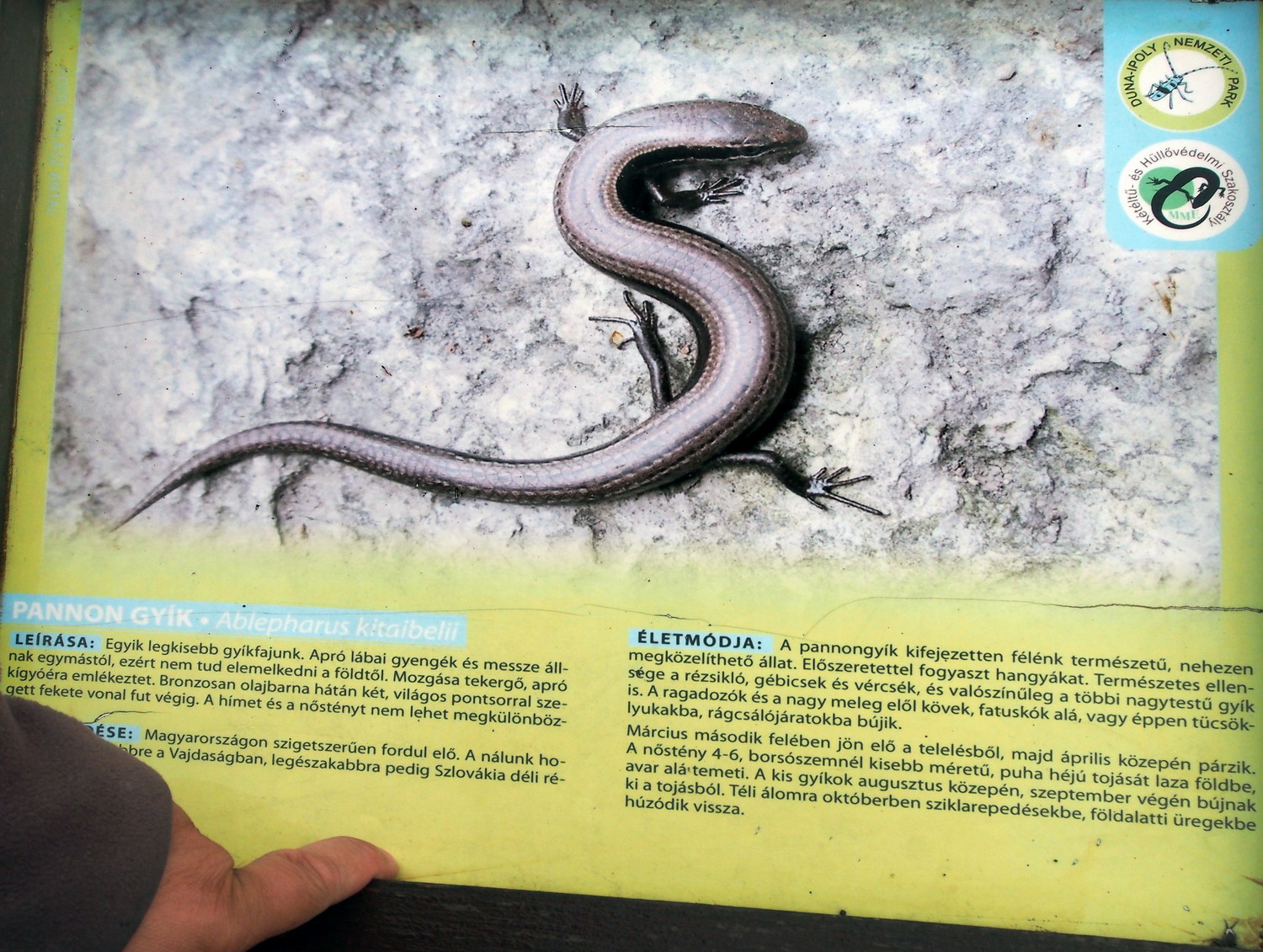

The snake-eyed lizard may be shy, but one can be sure to spot it on an information board

But there is another migratory species that come in large numbers: there were 2200 visitors in March of this year, while average annual visits reach 23,000. I asked Anna Vatai - teacher, local volunteer, and future manager of the Visitor Centre - is that too much for this relatively small area?

“We strictly control the movement of visitors while still offering them interesting programs to enjoy. For example, every May 10th we have ‘Birds and trees’ day for schools and kindergartens but it is a family program as well. To get back to the question: the most important thing is that the Sas Hill has been preserved when it was declared as a Natural Reserve, and its important species are now safe here.”

Csikófark (the joint-pine or Ephedra Dystachia) is a small Mediterranean shrub.

“The answer, my friend,

is blowing in the wind”

(Bob Dylan)

Now things become interesting: there are male and female plants. The ones in the Reserve are male while females, separated by the bitter destiny, reside on the Gellért Hill, one kilometre away as the crow flies. But even if they can never touch each other (poets would adore and use this a lot) the wind is their secret ally and courier that makes reproduction possible.

With Anna and Czaba, at the top of Sas Hill

The last DINP station: Protected area Great island of Racalmas

After a long cycling (and rainy) day across huge Csepel island, I came to a small bridge in Rácalmás village to meet with ranger Zoltán Kovács. We crossed the bridge to enter the Rácalmás island which is partially the National Park territory (4 ha) and Protected Area / Natura 2000 (356 ha).

Zoltán Kovács

"There are four islands on a 100 km long stretch between Budapest and Rácalmás and two of them are protected as Natura 2000 areas. This one is the largest and serves as a model of an ancient island on this part of the Danube. Two hundred years ago there were fields and people lived here. Then, due to migration to the cities, the island was deserted and today is mostly covered with forest. In the northern part, between the island and the left bank of the Danube, there is a swamp, suitable for aquatic birds.”

The owner of the island is the state, while the user is a forest company. They work here for 50 years now and Zoltán sees their influence as useful: “Working with us as partners, they helped to replace non-native poplar trees with original sorts on 70% of the island.”

Most protected species are plants but valuable ones include birds as well. There is one pair of white-tail eagles in the south part. Being here for 20 years they are old-timers but there is even a new generation now, two youngsters. However, they will leave soon as the parents will not tolerate competition.

Wild boar, red deer and fox are permanent residents. But they are not in a perfect paradise here because the island is a seasonal hunting area. It is also flooded on average every two years, and at such periods the space for these animals is reduced to the west coast.

The whole island is opened for visitors and offers a 3 km long trail at its northern end, used for recreation and for children's education (with the help of rangers). During summer it is possible to cycle around the island perimeter, but after days of rain, we were not able to even walk much further from the bridge.

On those 4 ha that belongs to the NP a small nursery garden was established, allowing for cultivating and research of various genotypes of black poplar:

“This was the original sort, but in the last 50 years, it seemed to disappear from Hungary. (It was not interesting for commercial use because it does not grow as fast as new hybrids, there are more side branches that make it harder to cut, and there was more waste during processing.) Then, within the DANUBEparksCONNECTED forest package, we had found the original black poplars here on the island and documented them by photographs and GPS points. We took genetic samples and sent them to appropriate institutes in order to successfully confirm that we have the right thing."

Thereafter, the LIFE program gave them a chance to establish another nursery with tens off different black poplar genotypes, while four hundred genotypes were collected along the Danube, in the territory of the NP.

|