|

The name "Wachau" sounds big and deep - with its right mix of vowels and consonants it resonates far and wide. But it actually marks a short, 16 kilometer long stretch of the Danube located midway between the towns of Melk and Krems: from Spitz to Loiben on the left bank, and from Oberarnsdorf to Mautern on the right one. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations of Lower Austria. The touristic formula of Wachau is simple and clear but hard to beat: picturesque landscape + historic villages + wine making tradition.

And Wachau also means slopes. Steep ones. Here the mountains rise right above the Danube, forming a narrow valley between Krems and Melk. Steepness is a character determining feature of the relief, steepness permeate the way of life. Vineyards of Wachau are steep ones. Pastures are steep. Paths are steep.

What is important to bear in mind in order to understand the great nature conservation significance of the Wachau? It is the coexistence of river landscape, dry grasslands (or “Trockenrasen” as mentioned in the previous reports - or “Brennen” in German), hillside meadows, natural forests, vine terraces and orchards.

Geological, climatic and landscape diversity is reflected in a species-rich flora and fauna. The different habitats are refuges for 300 plant species - among them 30 different types of orchids. Rare species of birds such as peregrine falcon, black stork, eagle owl, kingfisher and hoopoe can be seen, sea eagles are regular guests. Then there are beavers, 47 species of grasshoppers and emerald lizard - the heraldic animal of the Wachau - which inhabits traditional dry stone walls of the vineyards.

Let’s add to this that the Danube flows free on this stretch – there is no influence of power plant dams here. There are numerous gravel islands and banks and such structures, together with the old and revitalized arms/tributaries, promote the rich fish population with over 50 species. Remains of natural floodplains with flat riparian forests with softwood parts of white willow trees and precious (endangered throughout Europe) black poplars, accommodate more than 50 species of birds, rare bats and deadwood beetles.

No, bicycle was not of use here.

And no bicycle tool was of use here either - I got instead a pair of big cutters like these on the photos.

Touching carefully all the legacy and balancing its role and place in this touristy and wine micro universe, a team from LEADER-Region Wachau-Dunkelsteinerwald office covers a wide range of experience and specialist areas for the manifold tasks of regional cooperation. They will be my hosts today and I met them in front of their space located in the castle above idyllic tiny town-village Spitz: Mag. Hannes Seehofer is an project manager of nature conservation who works in the office since 2003, and Dl Elisa Besenbäck is here since 2016.

There is also a whole nice group of local nature lovers that will do some useful work on one of the protected dry grasslands (Trockenrasen). But as this is an area of steep Danube slopes, we will have to go high above the river to find one – that was different from my previous visits to dry habitats in Germany and Austria.

”In other zones there is usually one type of protection. But this region is not only about the nature - it is an indivisible combination of nature and man-made cultural landscape. That’s why it is protected on several ways: as an UNESCO world heritage, as an Natura 2000 area, while it is also recognized by its European Diploma for Protected landscapes” - says Mr. Kurt Farasin, an enthusiastic member of our group but also an Artistic Director of Schallaburg & Lower Austrian National exhibitions.

That is also why this is not a classic national park, despite the fact that since it foundation in 1990, nature and landscape conservation have a special significance in the region. The Wachau became a nature reserve in 1955, has been awarded the European Nature Conservation Diploma by the Council of Europe since 1994. and has been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2000. In 1972, the area around Jauerling was designated as Jauerling-Wachau Nature Park. The Wachau is part of the Europe-wide network of protected areas Natura 2000 (Fauna-Flora Conservation Area, Bird Sanctuary).

Soon after start we passed by this beautiful old house from 16th century.

(Most of the village dates from 11-12th century.)

The maintenance and care of species-rich dry grasslands and meadows is a major challenge for nature conservation. The Höhereck near Dürnstein is the largest dry grassland in the eastern Wachau with 200 different plants and about 100 species of butterflies. Typical for the Wachau dry grass areas are the feather grass (stone feather) and the large and the black cowbell. On the plateau of Jauerling and in its side valleys there are remnants of original lean orchid meadows.

We are hiding to Protected area Setzberg that has an area of 10 ha, from which 6 ha is an open (clear) space. The burning is a natural monument.

The microclimate in the area is a mixture of continental and Pannonian climate. And similar situation is with plants, except that during thousands of years even plants from Asia have found its way to here. The average rainfall is modest 300-400 mm per year, while Krems is one of the driest places in Austria. (Only 40 km away in direct line are the Alps, with about 1000 mm of rainfall per year.)

Walking up to the dry grasslands

The soil is composed of limestone, silicate and marble granite. “Dunkelstein” or “dark stone” has an magmatic origin as a mix of volcano ashes which got pressed in the sea bed. (Grey “clouds” in the white marble are actually the volcanic ash.) During long geological periods it was at least three times pushed to surface and sank back under the sea bed, meaning that it withstood three cycles of cooling down and heating before it became what we see today.

Removing invasive bushes in order to preserve open space for the dry grassland.

Our working place – Setzberg.

This hilly zone was populated in the past but, as many similar ones, was abandoned

after WW II: in that period the development of industrial agriculture led to drop of products prices and small farms were not able to keep with that pace. One such farm couldn’t support its family anymore, so someone had to get other job – and it started migration to cities.

The good consequence is that, since there is no more agriculture here, the whole region is a middle fertilized one. Why it is not completely free from fertilizers? “Because they still come by air”, says Kurt.

Fighting against invasive plants the way we do it today, on an area as big as Setzberg, off course wouldn’t have chance in long term. (Especially with someone like me in the band: while clicking and cutting around I thought of a possibility that it might end by being informed that I just cut the last remaining specimen of some region’s trademark plant :) That is why the Spitz team since 2010. used to organize 1-3 international summer work camps that gathered 10-15 participants from Europe, South America and Asia. During two weeks of work in the camp volunteers support the protected areas primarily in dry grass care and in the fight against neophytes, with the help of motor cutters or local farmers' mechanization.

“We now cooperate with other national parks like Donau-Auen and Thayatal at Chech border” – says Elisa – “and share these two weeks with them. We also organize another working camp with world heritage issues in cooperation with the Upper Middle-Rhine valley. It is a constant fight: we look for all possible partners and ways to enable financing of the camps.”

Despite being clearly marked as a nature monument, this steep part of the dry grasslands

are sometimes used by… mountain bikers who find it suitable for downhill ride.

After doing the job at Setzberg we started descend to Spitz but using different path. And here we were – the vineyard terraces, the core and hart of what made the viticulture of the region extreme but at the same time possible, determining it as the Cultural Landscape. A special feature is the fact that the walls are of the “dry” type: they were made without plaster, just by skillful stacking of stones. It all started at the beginning of the 10th century when monasteries started to cultivate vines not only on the valley floor but also on the steep slopes, by forming them into this impressive landscape.

Some incredible data about what I could see around me:

- visible dry stone wall surface area is ca 2 million square meters;

- total length of dry stone walls is ca 720 km.

The walls accumulate heat during the day and then during the night slowly release it in the sandy soils – something that vine likes a lot. It is necessary to continuously maintain them, while there are no many people nowadays who know how to do this ancient craft. But as it is now a cultural heritage the interest is growing and there are even regular courses for those who are interested in learning the skill.

The steep terrain requires much more labor than in vineyards on the plain as there are very few opportunities for mechanization. But even in the places where machines could be used they are deliberately omitted and work is still mostly done by hand (all Vinea winemakers are even obliged to hand harvest). Many wine growers are living on their farms which were built centuries ago, and much in the Wachau remains the same as it was in the far past, despite the pressure of modern times.

And it is not all about the wine. Using of concrete in the process of construction would reduce ecological functionality of the walls, but dry-walls are valuable, friendlier place for living things. That morning, when I asked how many different habitats are around here, my hosts said: “countless”. And now I understood why: the small cluster that can be seen on the photos above, consisting of a stone wall, a tree, some vine and some other plants - is just one of many islands in the sea of vineyards around me.

Each of these islands accommodate a variety of animal and plant species including even the Aesculapian snake, the largest native snake species in Austria.

Back to the castle office, Hannes shows his original collection of blades used in motor cutters during summer volunteer camps. Each year of hard work is marked by one worn-out blade and added to the collection :)

Then Elisa, Hannes and me cycled to Krems.

We first used ferry to cross to the right bank of the Danube. The ferry had unique feature: a Camera obscura installed as a part of an artistic project. Two huge simple lenses (shown by the arrow below) captured images of the surrounding space and sent them through a simple prism to the dark room where one could watch them on two simple optical screens. Despite the simple question “why should I sit here instead of simply going outside to watch the original”, there was that simple, inexplicable

magic of the pinhole cinematic effect that kept me inside for the whole ride… Ok, the simple coldness outside had a little bit to do with that as well :)

On the road with my hosts. Elisa prefers road bike – a beautiful classic

model with steel frame. Hannes rides more average horse, but his trump is this

enormously stylish “Aktentasche” that elegantly sits at the back of the seat.

By the way, let’s mention again something else besides wine: the region is

proud of its apricots and the name “Wachauer Marille” is protected in the EU.

While we approach the point where Rührsdorf side arm departs from the Danube, Hannes talks about its importance: “Our reason to be proud would be at the first place ten kilometers of side arms constructed or revitalized in last ten years through the ‘Life’ project funded by the EU. Here we implemented very important water measures in Rossatz-Rührsdorf area.”

The beginning of the Rührsdorf-Rossatz side arm

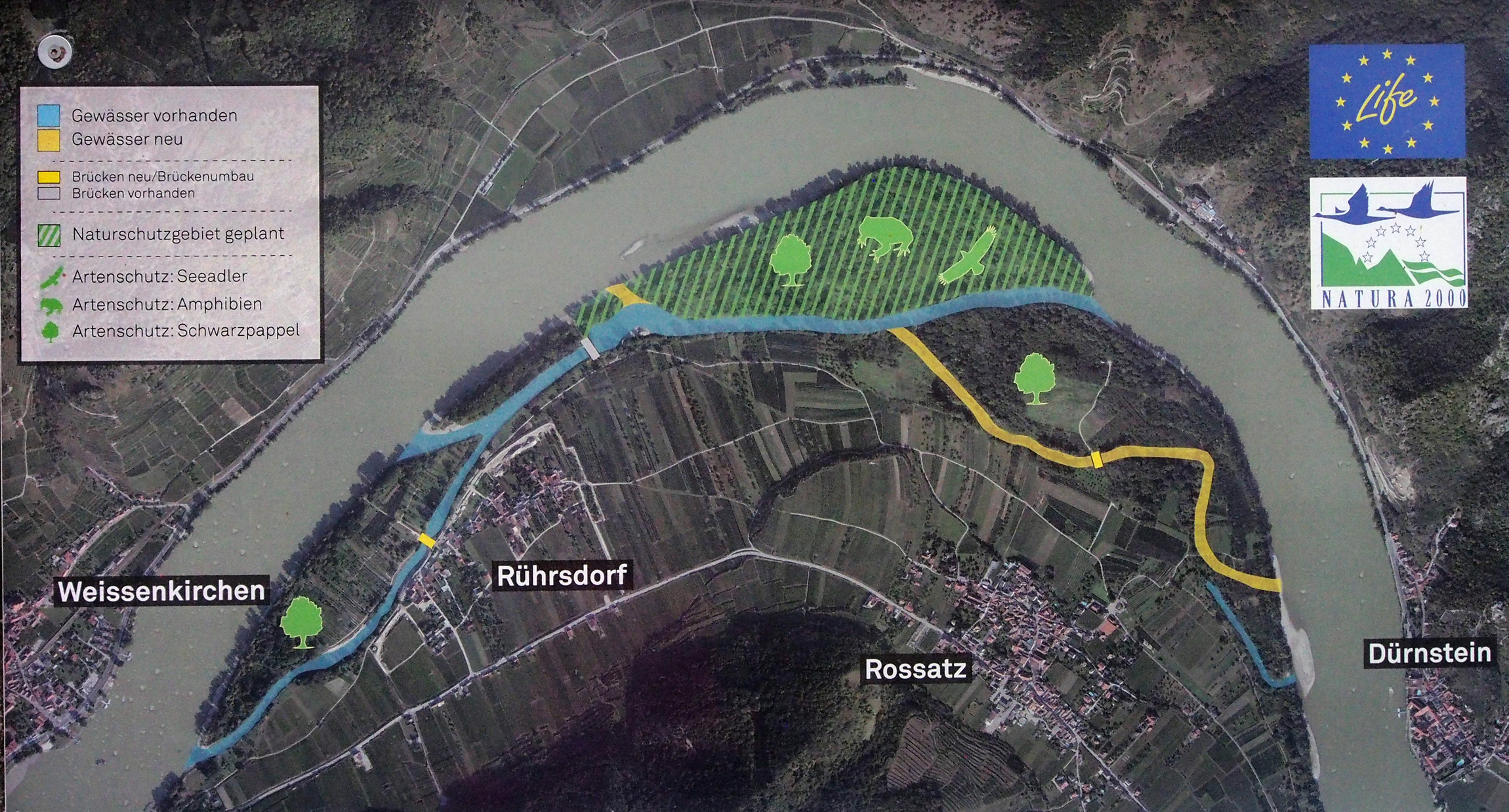

This info board shows what was done and what is planed in the system. On the map below:

- Blue color – already finished side arm;

- Yellow color – planned new side arm;

- Green hatched zone - planned nature reserve with eagles, amphibians and black poplar.

This is where a new offshoot will be cut to the Danube (the short yellow line on the map above)

to provide enough water in the system when the new side arm is finished (the long yellow line on the map).

„There was an alluvial forest there and we want to have it back, mostly because of fish – the water will be calmer and more convenient for their reproduction, spawn, etc.”

Private land owners are an important part of such plans and most of them are open for cooperation, but it doesn’t always go without glitches. The planned new side arm is one example of that:

“Beavers recently damaged one orchard and fresh image of his damaged property makes the land owner worried that the new sidearm would bring even more of them. That’s why he opposes the project at this moment and we will need some time and some good arguments to change his mind.”

Hannes states that the ecological awareness in the region is high: ”There was plan in seventies to build a new dam between Dürnstein and Rossatzbach. But strong public reaction prevented it, and this movement actually become the base for world heritage and the rest of the story here.”

But he also adds this note: “Local people pay more attention to more visible aspects of the values we have here – and that’s mainly terraces. Less respect is given for subtler things like burnings. It also depends of the interests: hunters support us to maintain dry grasslands because they love open spaces. On the other hand, rock climbers often disturb the rare Falcon Peregrine who makes its nests in rocks and cliffs.”

Within the frame of the DANUBEparksCONNECTED in the last three years Elisa and Hannes visited Donau-Auen and Duna-Ipoly National parks; Elisa had the opportunity to also see Kopački rit, Rusenski lom and Djerdap, while Hannes visited Prut and Persina.

Elisa thus has good ground to conclude this: “Important thing that we learned through the project is that the challenges are similar. There are different ways to approach them, but there is no need to invent the wheel again and again - we can learn a lot from the experience of others. “

|